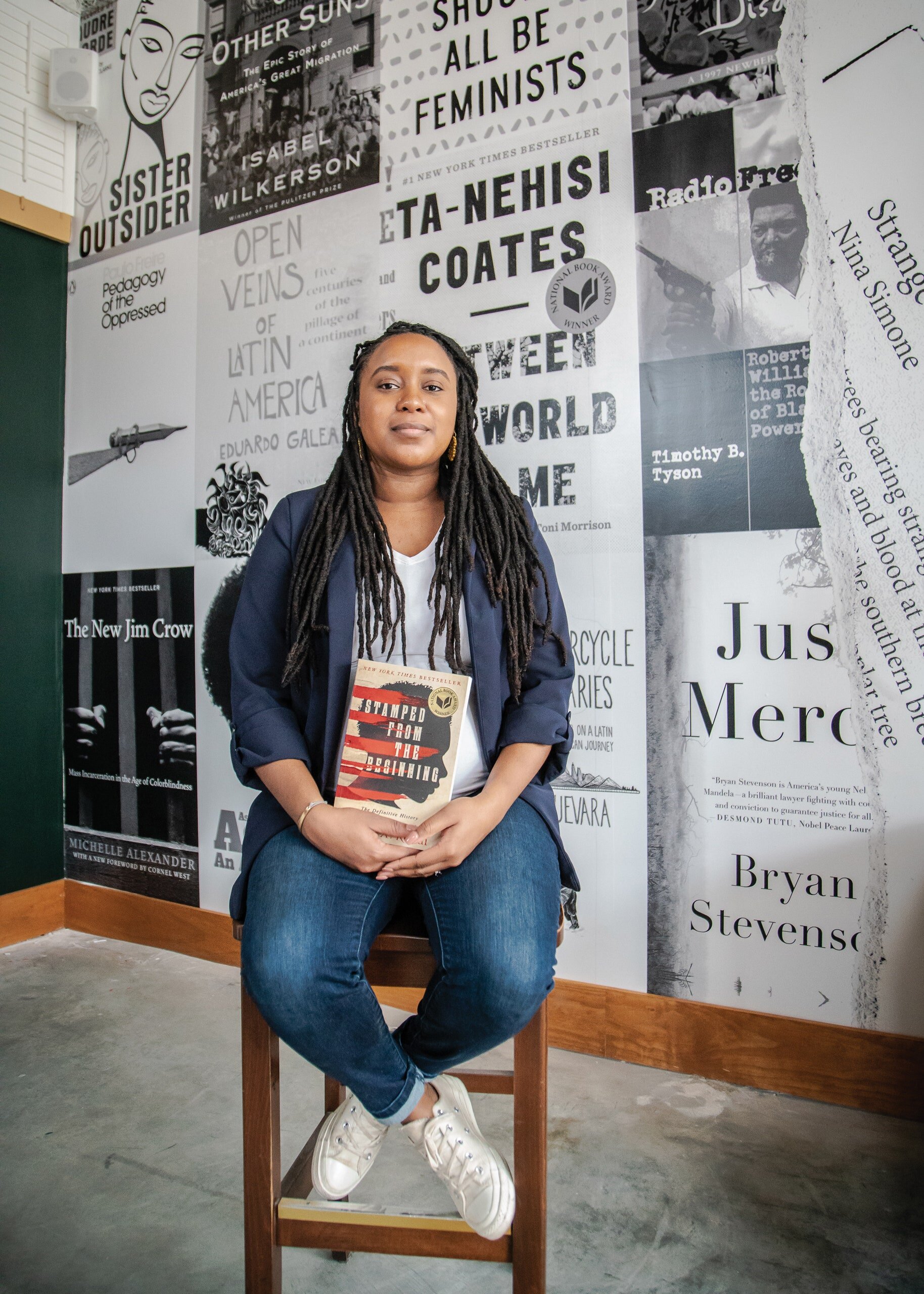

Onikah Asamoa-Caesar, of Tulsa, has been facing the same challenge of many Black bookstore owners in this moment of racial awakening.

Photograph by Greg Bollinger / TulsaPeople Magazine

When Onikah Asamoa-Caesar saw people arriving at Fulton Street Books & Coffee, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, an hour and a half before its grand opening, in July, she grew nervous. The launch of her new store was supposed to be a quiet affair. She’d asked some of her friends not to show up and had stopped promoting the date on social media weeks earlier. The number of coronavirus cases in the city had been rising steadily for a month, and she didn’t want to risk people contracting the virus in a crowd of her making. But, in the wake of protests over the killing of George Floyd, many people were seeking a salve for the more enduring ailment of racism in America. They came to Fulton Street to find it. “There was something unique about being in a pandemic that allowed people the space to pay attention to what was happening,” Asamoa-Caesar told me. “The question I kept asking myself was, ‘Why is everybody wanting to read now?’ ”

Asamoa-Caesar was facing the same challenge of many Black bookstore owners in this moment of racial awakening: there were simply too many people wanting too many books. The night before Fulton Street opened, the floor of the store was covered in boxes, containing a thousand copies of Richard Rothstein’s “The Color of Law” and another thousand of Ijeoma Oluo’s “So You Want to Talk About Race.” The books were part of the Ally Box, a subscription service that Asamoa-Caesar created in response to the killings of Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Each month, subscribers receive two books dealing with race, Fulton Street-branded educational resources, and opportunities for online discussions with peers and scholars. The first box included a series of flash cards with definitions of terms that many people feel uncomfortable uttering aloud, such as “white supremacy,” “anti-Black,” and “racism.” Asamoa-Caesar had hoped that a hundred people would buy the eighty-dollar-a-month subscriptions; she quickly sold nearly fifteen hundred and had to start placing potential customers on a waiting list.

Asamoa-Caesar stayed at the store until 2:00 a.m. preparing for the opening day and stored the Ally Box books in a friend’s garage for safe keeping. When the doors of Fulton Street officially opened, at 11:00 a.m., the airy space looked like it had always been Instagram-ready. A wall of the one-room store is lined with themed bookshelves focussed on hip-hop, history, and feminism, among other topics. The opposite wall is dominated by large black-and-white covers of books that Asamoa-Caesar holds in particularly high esteem—“The Warmth of Other Suns,” by Isabel Wilkerson, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” by Paulo Freire, and “We Should All Be Feminists,” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. At least seventy per cent of the store’s titles are written by or prominently feature people of color. “Often times, our voices and stories are not a part of what’s considered ‘classic’ literature,” she told me, as we walked past the colorful bookshelves. “It looks different, but to me, to us, these are also classics."

For decades, Black-owned bookstores have played a vital role in Black neighborhoods, serving as venues for both education and activism. Though they, like other independent bookstores, fell into decline during the rise of Amazon, with more than two hundred and fifty shuttering between 1999 and 2014, they’ve seen a surge in popularity in recent years amid the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. What’s happening this summer is new, though. Stores have reported sales boosts as high as four hundred per cent. Owners are working around the clock to fill a crush of orders. Stores that were once community-gathering spaces for Black people are now centers of intellectual triage for white people.

Asamoa-Caesar is searching for the equilibrium between these two needs. Her literary taste, and her passion for history, were shaped by a childhood split between the sunny veneer of multiculturalism in Southern California and the sinewy roots of racism in the Deep South. In Hazlehurst, Mississippi, a small rural town where she spent some of her teen-age years, racial contradictions were ambient. Every day, she observed white flight in her segregated high school, where the class graduation photos lining the hallways transitioned from all-white to all-Black as the years went by. In California, where she returned for college, the contradictions were more disruptive. While attending California State University, Fullerton, in Orange County, a carload of white boys yelled “nigger” at her and her friends as they walked to their first college party.

Black people are often forced to process these experiences in silence. By studying history at Cal State, Asamoa-Caesar learned what many people are discovering this summer—that racism is and has always been an ideology taught, legislated, and profit-maximized at enormous scale in the United States, not a series of individual slights that victims must bear with quiet dignity. “As a high-schooler, I saw the Confederate flag, I saw the segregation, but I didn’t have the language to describe what I was living,” she told me. “History gave me the language to articulate my experience, and why I was having that experience as a Black person in this country.”

Language seemed to be the thing the patrons of Fulton Street were searching for on the shelves. “White Fragility,” by Robin DiAngelo, overshadowed all the other works, literally, with hundreds of copies running clean across the length of the store on its top bookshelf. Below it were nearly as many copies of “How to Be an Antiracist,” by Ibram X. Kendi. (Combined, the two books sold nearly eight hundred thousand copies in the U.S. in the months of May and June.) “As a bookseller, it feels good to see books flying off the shelves,” she told me. “I also can’t let go of the fact that we have to go beyond just reading.” The current Ally Box includes both DiAngelo’s and Kendi’s titles, along with a list of recommended direct actions that subscribers can take after reading, such as registering to vote or donating to a Black-led nonprofit.

One of the customers on opening day, Tara Rittler, a white woman who has lived in Tulsa since 2004, purchased “How to Be an Antiracist” and some children’s books for her five-year-old son. She listed off a number of books that she’s read that helped her understand racism in theory—“Just Mercy,” “The New Jim Crow”—but said that she was hoping Kendi’s book would help her figure out how to navigate conversations on the subject. She’s wary of antagonizing her conservative relatives in Kansas, even on Facebook. “I’m not super-active as far as being proactive about being anti-racist,” she told me. “I like reading books and education. Actually doing the work is a lot harder.”

Kyra Manlove, a young Asian woman who came to Tulsa for college, picked up a copy of “White Fragility.” Although not white herself, she was raised in a white family and said that she had internalized some aspects of white culture, which she wanted to examine. She was aware of the growing backlash against the book, which was written by a white woman and has been called “condescending” toward Black people, but she said that she saw the value in it. “While I don’t think it’s great, I think there is some merit to having a white lady explain it to other white ladies, because they have a similar frame of reference on some of these things to help them understand,” she said. “But it shouldn’t be the end all, be all.”

Not everyone ventured to Fulton Street seeking a lesson on race. Just outside the store’s entrance, a pair of Asamoa-Caesar’s friends were discussing the successful opening. One of them, Alexander Tamahn, a local artist, had painted a large mural of Nina Simone, Audre Lorde, and Frida Kahlo that adorned the bookstore’s eastern wall. (He plans to add temporary face masks to the figures this week.) Tiona Bowman, an educator from Tulsa who now lives in Dallas, had helped pack the huge number of Ally Boxes. Bowman raised the book she had just purchased, the novel “Speaking of Summer,” by Kalisha Buckhanon. “I’m very woke. I’m very aware,” Bowman said. “I don’t really need to read too many more books about ‘How Not To,’ or ‘How To.’ ”